Short Stories

There’s so much to say about Madagascar. Here are some short comments about small events and the intricacies of the Red Island.

MAF

Early in my trip I met one of the Mission Aviation Fellowship pilots from Germany, Jakob. He told me that I could go flying with him sometime when he had an open seat. Loving everything aviation, that sounded great to me. David dropped me off at the MAF hanger early one morning. I watched as the local workers loaded the plane with UNICEF vaccines as we waited for the early morning fog to clear. Once the outlook was clear, Jakob and I boarded the plane and headed off.

It was a beautiful day to fly (5 years later I would get a pilot license of my own). The sky was clear and the visibility was infinity. We cruised west over the central highlands gazing down on the endless strings of rice terraces and the red dyed rivers, bleeding the island into the sea. Our first stop was Nosy Varika, which isn’t actually a nosy (island) but a small down on the east coast of M/car. After circling the town and making a low pass over the runway (to scare off the cows), we made a 180 and landed on the long grass strip. Instantly upon parking, we were surrounded by at least 75 people, all amazed to see the plane in town. Despite all the people, no one wanted to help unload the plane, so Jakob and I unloaded it ourselves as the crowd watch.

Having half the planed unloaded, we packed up again and flew off to our next destination, Marolambo. This is a small village in the mountains, about halfway between Tana and Nosy Varika. We circled the town as we lined up for the airstrip, admiring the convergence of two rivers and the rapids and waterfalls that surrounded. Joking with me, Jakob asked me to tell him when I was able to spot the airstrip. Even as we lined up on final, I was still not able to find it. It turns out, the runway was little more than slightly smoothed and cleared portion of a hillside, that during the dry season, blended in with the brown, bordering brush. I could hardly believe we could land a plane there.

Here we unloaded the last of the supplies, with the help of the locals who were much more eager to unload than in Nosy Varika. They even brought us some bananas for a snack on the home. After unloading we hopped back in and flew into Tana. On this trip, I was also able to vividly see the pollution surrounding Tana. As we approached the city, we could easily see a brown layer of smog hovering over the city. Once landed, I hung around the hanger until David came back to pick me up.

Sunday Evening Fellowship

Sunday Evening Fellowship was a weekly gathering of the missionaries and other ex-pat Christians in Tana. This is where I got to know people like Jakob above, and Nate and Scott with whom I took the Christmas trip. The missionaries would gather at someone’s house on a rotating basis, and just fellowship and hang out while having a short Bible study. It was a nice break from the often tediousness of living in a developing country, and a chance to speak English at a normal pace.

Hotely

Bus rides between towns on a taxi-brousse are long. Really long. Long enough that you need one, two, or three meals to survive them. A taxi-brousse, however, is no place for packing a picnic in an igloo to sustain yourself for the 20 hour trip (not that I had an igloo cooler or even a lunchbox). So, strategically placed along all the major bus routes are Hotely, loosely translated as: fast-food-restaurants-on-the-side-of-the-highway-that-serve-leftover-rice-and-overcooked-loaka-to-the-poor-people-packed-into-taxi-brousse. Hotely’s are of such disrepute, that some of my Malagasy friends would not eat there when taking the bus. I never gave it a lot of thought (purposefully) and ate whenever my bus would stop at one. I would typically order chicken and white beans which always tasted good and was less overcooked than other dishes. When eating Malagasy style, you get one bowl of rice, one bowl of stuff-to-put-on-top-of-rice (loaka), a spoon and a fork (no knives). You eat your loaka, gradually mixing in the rice until the loaka is done. Never would you eat rice plain. Supposedly, whatever rice is leftover in your bowl, gets thrown back in the pot at the Hotely. Needless to say, I always prayed a fervent prayer of blessing before eating at a Hotely.

Sanitation

Sanitation is non-existent in M/car. It is not uncommon to see someone squatted on a sidewalk, or relieving themselves on the side of a building. Contrary to most cities in the world, in M/car it’s often cleaner to walk in the gutter than on the sidewalk, as the sidewalk is far more likely to have been defecated on. No matter what, always watch your step when walking.

School uniforms

All school children must wear uniforms. In M/car, this means smocks. Every school has their designated color/pattern of smock, designating their school. When walking through town, you often see gaggles of little kids all dressed in the same pink, green, blue smocks. Little kids whose parents dress them have their smocks buttoned up to the top. Cool teenagers wear their smocks baggy and unbuttoned. Even far out in the country, such as at Andringitra, the school children wear their smocks.

City Buses and Taxis

Most of the time I traveled around town, I took a bus or walked. There is no government-run bus system, so proprietors run their own buses. Each bus has a number and a route they travel. Typically, two or three bus numbers will run each route, with dozens of routes circling the city. There are, of course, no bus maps or information to tell you which bus goes where, just a young man on the back of the bus yelling out neighborhood names. Andravoahangy! Antanimena! Ampefiloha! Analakely! Learning to navigate the city is often a trial and error process. More than once I had to jump off a bus after realizing it turned the opposite way from where I wanted to go. The buses are not large and seat five to a row with at least seven rows, it often stifling heat and an even more stifling scent.

When tired of the bus, a taxi is the next best option. There are two rates for taxis (and everything else) in M/car, the local rate and the foreigner rate. After a few months, you learn the local rate for things and negotiate for that rate. Negotiating a taxi involves four steps: (1) Picking a taxi driver. All taxis hang out in a bunch, so as soon as a foreigner approaches the bunch, all the drivers rush in. Quickly picking a driver is key to avoiding a riot. It’s also important to pick a driver, and not one of the random guys hanging around trying to drum up business for the drivers. (2) Telling them where you are going, for instance, Amboditsiry. At which time the driver stares blankly and gathers the other drivers together to ask where to go. (3) Negotiating a price, which is always inflated, and negotiation length varied with my energy level. Sometimes, if I was with a local, I would have them walk ahead of me and negotiate a price, then I would come up from behind and jump in the taxi, much to the dismay of the driver. (4) Stop at the nearest gas station. All taxis are perpetually out of gas. This is partly due to their lack of money, and need for an advance on the cab fare before taking you to your destination, and partly due to the fact that the gas tank is an empty 1.5 liter water bottle kept at the feet of the driver, with a small tube running to the engine. With the water bottle filled, you are free to go to you destination, often picking up additional passengers on the way.

In Tana, city law dictated that all taxi’s be painted a dull tan color with no additional decorations. Outside of Tana, Taxis were free to paint and add decorations as they saw fit. Which usually meant as many decorations as possible. Stickers on the windows, lights on the roof, multi-color paint jobs, anything. All in the hope of picking up more passengers. In Tana, the number of passengers was also limited to the number of seats (about 4 passengers). In other cities, particularly on Nosy Be, passenger count was unlimited. I believe the most people I ever rode with in a taxi was 11: four men including the driver, two women, a mom and her four kids. The taxis in M/car are not big, typically a decades old Renault 4L or Citroen 2CV. These cars are barely drive-able and held together with bailing wire and will power.

The taxi-brousse

Taxi-brousse are the bush taxis that take locals and frugal foreigners between cities. This was my main form of travel when in M/car and I had little money and an adventurous spirit. A bush taxi in M/car is about the size of a common mini-van in the U.S., perhaps a little longer, that has been converted into an 18-passenger van (read: no personal space or leg room). All the bags are stacked in multiple layers on top of the bus.

There are bus stations in each large city in M/car, with the largest cities having multiple stations depending on the direction you are traveling. Smaller villages will have a designated spot on the road where you can hang out and wait for a bus with an open seat to pass by. Arriving at a bus station is much like picking a taxi. Each bus company has a rickety wooden booth set up, all in a line, with buses parked in back. As soon as a foreign gets near the station, a mad rush of men engulf you. They are all yelling and grabbing at you and your bag, surrounding you in confusion. To add to the chaos, none of these men technically work for any of the bus companies, but receive some kind of finder’s fee from the bus company for directing passengers to their booth.

You can make reservations and buy tickets ahead of time, which I did when traveling from Tana, as it assured that I could get a seat with the maximum leg room. But, you could also just show up and book a ticket on the next bus leaving. Doing this is a bit tricky, because all the bus companies say that their bus is about to leave, but really, the bus doesn’t leave until it is completely full, regardless of what time they said it would leave. So you have to accurately discern which bus is actually full in the midst of a crowd of yelling Malagasy.

No matter what, the buses always take their time leaving. You’re guaranteed to be waiting at the bus station for at least a few hours. My rides on the taxi-brousse ranged anywhere from 4 to 20 hours. 10,15,20 hours on a packed 18 person mini van is more than enough time to sap every bit of sanity out of you.

A Perpetual State of Decay

M/car is in a perpetual state of decay. The moment a building, road, port, railroad, boat is initially completed, that is the last maintenance that is done. Each building looks like it did when it was built, but with the paint chipped and faded and worn. The plaster failing in places. Each car is improvised just enough to keep it running. The roads wear away until the asphalt is no longer visible. The reason for this is mainly economics. Maintenance is expensive. So the bear minimum is done to keep things operational. Part of it is culture. Maintenance is not an emphasized cultural norm. Part of it is probably religion. The traditional ancestor worship stresses keeping things the same as they are.

Sadly, the environment of M/car is also slowly decaying. Most of the forest are gone, and the summer rains erode more of the island, and its rich farmland, each year. From above, the rivers look like they are bleeding the island into the sea. Since the coup in 2009, it has only gotten worse, as what little environmental protection that existed is now gone. Without forests, there is no water table. Without soil, there is no farmland.

Land Rovers

Tom and Lauralee two Land Rover Defenders, two door, turbo-diesel. They were awesome, exactly the kind of vehicle you would expect to drive in Africa. They felt invincible. So powerful they could so anywhere, over any terrain. The road to our compound was rough, especially during rainy season, and Land Rover was often needed just to get home. I loved driving the Defender.

Ampefy

In the fall, Nate, Scott and I took nine boys from the youth group to Ampefy, a small town on a lake west of Tana for a weekend camping trip. We loaded up on a Friday evening and drove out to Ampefy. After eating at a restaurant, we set up camp late that night on a small river running from the large Lake Itasy. The weekend was a good time for me to get to know Nate and Scott as well as some of the youth.

During the weekend, we swam a lot in the river (supposedly the lake has crocodiles, but that’s what said about every lake in M/car) and hiked around the lakes and rivers and villages. We ate most of our meals at the same restaurant and also spent some time there playing ping-pong and pool.

The highlight of our trip was on Saturday, when we drove a bit up down the river to the Chutes de Lili, a 60-foot, beautiful waterfall. The roar of the falls make them seem bigger than they are. We hiked around the falls and the river, led by a couple local kids who were self-designated as our guides. We swam in a few slow spots in the river and enjoyed the warm weather and water, before heading back to camp.

On Sunday afternoon we loaded everyone back into the bus and headed home.

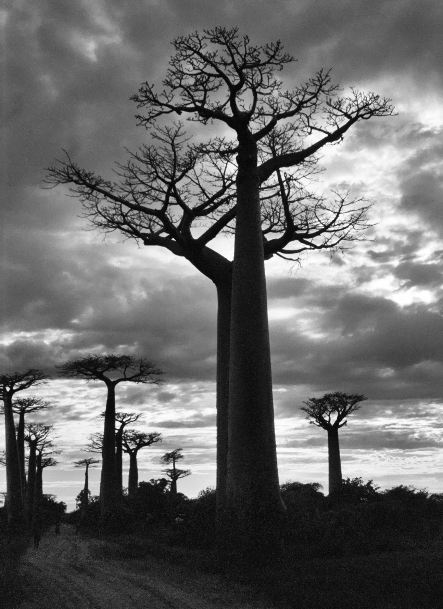

L’Allee des Baobabs

I took a trip to Morondava, solely for the opportunity to see the Avenue of Baobabs. There are eight species of baobabs, six of which are endemic to Madagascar. One of these six is the most magnificent of them all, the Grandidier’s baobab, which grows proudly and prominently along a small dirt road just outside of Morondava, known locally as L’Allee des Baobabs.

As with all my adventure in M/car, mostly due to my lack of travel funds, getting to and from there was an ordeal to be endured. Going there was bearable. Pastor Tom and Pastor Richard were already planning a trip there to visit the church, and I was able to ride along, and therefore sleep in the back of a Land Rover, rather than fighting insomnia, upright, squeezed between two Malagasy bewildered as to why a vizaha would ride the taxi-brousse.

Morondava had once been a fairly busy port city, but as the road between Morondava and Tana slowly deteriorated, shippers were less likely to use the port. Eventually a series of cyclones destroyed what remained of the port, ending use of it for good. Since that time, no work had been done on the road. For a good 125km or so, the road was a washed-out, pot-holed mess, requiring 5 hours to cover. The majority of the length of the trip seemed to be in this middle section of road.

Morondava didn’t strike me as a town visited much by anyone. The only tourists would be those going from the airport to the baobabs, then continuing on to the Tsingy de Bemaraha, a location I was unfortunately unable to visit. There were few hotels and dusty streets, busy with activity only in the mornings and late evenings. The heat of this corner of M/car prevented anyone from being out during the day.

When I first got there, I tried to find a 4-wheeler or motorcycle to rent to take to the baobabs. My lack of funds made me settle on paying a taxi driver. I found one hanging around town and arranged for my trip early the next morning.

I got up before sunrise and met my driver and we headed out-of-town. The Avenue of Baobabs, and what makes it so picturesque, is the result of poor maintenance and disregard for the value of forests. The whole area was once covered in forests, the 10 foot thick and 100 foot high baobabs only the kings of a vast array of tropical trees. The forests are long gone, the baobabs remain only because of their spiritual significance, and the generation of tourist income. Agriculture and grazing continue to creep in on the few remaining trees, that are still unprotected in a country with a fractured government far from being focused on conservation.

The trees rise from an otherwise barren landscape, seemingly growing upside-down, with their roots reaching for the heavens. A dozen or so line the red-dirt road forming the famous “Avenue” but a few others can also been seen in the distance. Several people were traveling the road, carrying out their morning chores. Women walking together, a few zebu-drawn carts, and even a Chinese group setting up their model for a photo shoot with the trees.

My driver took me around the area, giving me time to take pictures and taking me to the “Lover’s Baobab,” two trees that had grown twisted around each other.

With little else to see in Morondava, and without transportation to Tsingy, I got back into town from my excursion, and went to the taxi-brousse station to arrange my trip back to Tana. I got my ticket for the late afternoon of that day. This trip would be the longest bus ride of my stay in M/car. After leaving in the late afternoon, I arrived in Tana, the next day, 21 hours later. While most buses had at least one back up driver, this bus had none, requiring one driver to make the trip on his own. Because of this, he took frequent and long breaks. This combined with the painfully slow, unimproved portion of road (which took 7 hrs to cover), made it an arduous trip. I was joined on the bus by a random Yugoslavian guy, who drank the whole time and never ate. It was uncomfortable, but it was my way to see the island.

Just a Five-Hour Truck Ride

Though not many, there were several non-French expat families living in Madagascar, particularly in Tana. The kids came from a wide variety of families, backgrounds, countries and schools. Embassy workers, NGO workers, missionaries, American School teachers, business owners, etc.

Life as an expat kid can be exciting: friends from around the world, experience in a foreign culture, learning new languages. Life can also be difficult, especially for kids of government workers, who may move every few years, leaving friends behind and forced to make new ones. It can also be difficult for those that left their home country later in their childhood, leaving a lot of established friends behind.

Of the many great things about growing up in a foreign country, the pure adventure may be the best. A young couple living in Tana,; one a pastor from South Africa (Hennie), the other an American missionary kid who had grown up in M/car (Shelly); had started an outreach to the kids, organizing monthly hang-outs, trips to the favorite coffee shop, and best of all: the annual youth trip.

The year I was there, the trip was to Mahajanga, Shelly’s hometown, where we would (theoretically) spend the majority of our time camping at a waterfall outside of town. Our trip started by taking a bus (which of course arrived late) from Tana to Mahajanga, about a 10 hour trip. When the bus arrived to pick us up, we quickly realized that it had spent the previous day hauling loads of fish. It took several hours of the drive before we no longer noticed the stench.

The 10 hour drive went fairly quick, and I took the opportunity to enjoy the scenery of the central highlands. We arrived in Mahajanga late Saturday night, and made home at Shelly’s parents house. Sunday was Easter so we had a short service, then spent the afternoon hanging out at the beach. Monday morning our real adventure began.

Early in the morning, all 20 or so of us loaded up our gear and ourselves into the back of a large lorry for a five-hour drive to the waterfall where we could camp for the next few days. Starting out, even early in the morning, it quickly became hot and uncomfortable in the back of the truck. But for five hours, we could endure anything.

An hour and a half into the trip, we got stuck for the first time. All of the back tires were buried up the axles in mud from the rainy season. The biggest hindrance to getting unstuck was the fact that all the tires on the truck were bald. Through the course of our trip, several tires on the truck became so worn, that there was little more than threads holding them together. Truck tires are expensive, maybe $500-$1000 each, in a country where most people make only $300-$400 annually.

The next four hours were spent digging out the back end of the truck. Through this, I learned the Malagasy method of getting out of the mud: dry sand. No matter how the truck was stuck, the driver and his helper’s answer was dry sand. Everyone would dig the tires out of the mud, then promptly bury them in dry sand. However, dry sand or wet, with bald tires its hard to go anywhere.

In the truck, we had with us four live chickens that would later be our meals. The stress of baking in the back of the truck during those four hours caused one chicken to start laying eggs, and another chicken to die. We made a small dish out of a water bottle and attempted to feed and water the remaining chickens in the hope they would stay alive long enough to become dinner.

Eventually, after a lot of pushing and digging, and at the expense of a chicken, we got out and back on the “road.” After a couple more hours of driving, we came to a river and took a break. We all had a snack and jumped in and swam. A small concrete dam had been built across the river to serve as a bridge, creating a beautiful swimming hole and a welcome break from the back of the truck.

After a half hour of relaxing, we loaded back in the truck to finish our trip to the waterfall. We drove across the dam and onto the sand on the other side where we immediately became stuck. Ironically, we were now stuck in dry, beach-like sand. The driver and his helpers stared at each other confounded. Their only previous solution to getting un-stuck was dry sand. Now stuck in dry sand, they had no way out. Despite this, one of them still offered up the solution of burying the tires in dry sand.

Luckily, after about an hour of brainstorming, another truck passed by that was able to pull us out. However, by this time, it was around 5:30 and nearly dark, so we decided the beach would be a good place to spend the night. It turned out to be really great. It was warm, the swimming was fantastic, and the sand was soft and comfortable for sleeping. We all had a good time.

The next morning, we repacked and loaded back into the truck. We were all still expecting just a few hours left to go. It wasn’t an hour out of camp before we were stuck again, for a third time. Perhaps rainy season was not the best time of year for traveling dirt logging roads in the grasslands of Madagascar, but the weather was great for us, and the scenery and greenery amazing. It just meant getting stuck in the mud. A lot.

This time we only spent about three hours, gathering rocks and cutting down trees, trying to find anything we could to throw under the tires for traction to get the truck out of the mud hole.

What amazed me during the whole two day trip, was the fantastic attitude of the kids. If this had been in America, it would have been nothing but incessant whining. Though two days in the back of a truck seems extreme, even in hindsight, at the time, it seemed almost normal. This was just how things go in Madagascar. Everyone knew it and dealt with it. It was frustrating at times, but expected, and everyone enjoyed it and had a good time.

After getting unstuck, we continued our journey. Now deep into the bush, Shelly, our guide, began to realize that a lot of new logging roads had formed since the last time she had been out there, and began to lose her way. We spent a lot of time testing roads trying to find our way. Then we got stuck again, for our fourth and final time.

This time was inexcusable. It was almost as if the driver drove directly into a ditch on the side of the road and dumped the front wheel in it. Even the driver’s helpers gave up on him and took a nap under some trees. The driver was either crazy or blind, or both.

While the driver worked on digging out the truck, I took a walk up the road. While walking I discovered one of the more sinister insects of M/car. I don’t even know what their called, like horse flies, but nearly impossible kill and relentless. They began attacking my legs, at least a dozen of them, immediately latching on and digging into my skin. No amount of swatting could keep them off, so I just ran. I ran until they were gone, hoping not to see them again.

Somehow, I wasn’t paying attention, Todd was able to dig the truck out. After a lot of revving, spinning of tires, and pushing, we got the truck out. Now, it was only a matter of finding our way to the waterfall. With the truck low on gas and Shelly at her wit’s end, we found the waterfall just before sundown on our second day of travel.

It was beautiful. We camped on the smooth rock next to a trickling creek, above a magnificent 55-foot waterfall. There were trees all around us and a huge pool to swim in below the waterfall. That night we set up camp and swam in a few pools above the falls.

We also had our first real meal in two days. In addition to riding in the back of a truck, on hot summer days, that we had to dig out four times, we also barely ate. We had some small sandwiches for lunch and some beans for dinner the first day, and nothing but some slices of banana bread for breakfast the second day. That night, we ate chicken and beans and rice, and it was maybe the best meal I have ever ate. The next morning we ate the leftovers for breakfast and it was still amazing. We were all just so tired and hungry.

Camping in the bush was a special treat, because M/car is a country with few city lights, and being in the bush, were even more removed from any trace of artificial light. The stars were bright and clear, brighter than anywhere else I’ve ever been. The added treat was seeing the stars of the southern hemisphere, different enough that it’s noticeable, compared to what I’m used to seeing in the states.

First thing in the morning, we drove a short 30 minutes to the Anjohibe Caves. This cave is truly in the middle of nowhere and rarely visited. The first thing you come to before entering is a small patch of concrete and a flagpole. According to rumors, the caves had been used by French soldiers at some point in time, and possibly also be Malagasy soldiers, though I can’t imagine what they would be fighting or defending out here. At some point around WWII, the cave had been fitted with electric lights, which is phenomenal, considering you can barely get reliable electricity in the capital. However, I don’t remember them working at the time, so maybe not so phenomenal.

Which brings up another funny thing about M/car. Electricity is so fickle anywhere you go, that you spend much of your time inside using candles for light. During my time there, the electricity would go out 5-6 times a day for anywhere from 15 min to several hours. Many of the missionary wives would comment that their idea of a romantic dinner was one with all the lights on, as candlelight dinners were so commonplace.

Once inside, the cave, we were amazed. It may be the most unique cave I have ever been to. Most of the caves I had been to were in the Pacific northwest are old lave tubes, smooth and without mineral formations. This cave was completely different. Stalactites and stalagmites were everywhere. From floor to ceiling in all parts of the cave. We wandered in and out of all the tunnels, exploring as much of the cave as possible, gazing at the rock formations. Part of our exploring was also a race to find the entrance to an underground river.

The entrance was little more that a crack at the bottom of an obscure wall. One at a time we slid down through the crack and into a cavern holding the river (or maybe just a lengthy pool of rain runoff). We walked out of the caves through the river, which was about 500 yards from where we jumped in to where it came out in the open and completely dark. The water was mostly waist deep, but there were few places that we needed to swim, helping each other along with the few flashlights we had available. Sharp rocks littered the bottom of the river and all our legs were pretty cut up.

After hiking back to the main entrance of the cave and grabbing our stuff, we headed back to camp for lunch. One of the driver’s helpers, we called him Rasta because of his dreads (generally, anyone with dreads goes by Rasta in M/car), tagged along with us all day and had the time of his life. The whole time we were exploring the cave he was talking non-stop. When we found the entrance to the river, he was the first to dive through the crack , even before we could get flashlights. Later that night, he continued to talk non-stop telling anyone who understood Malagasy about his day. When some of the kids were dancing around the campfire, he was joining right in.

After lunch we went down to the pool below the falls to swim. To get to the pool, we had to climb down roots of trees sticking out from the side of the cliff. Once down, we all jumped in. The pool was pretty deep, but littered with large boulders just below the surface.

After swimming for awhile, a small group started walking downstream, crawling up and over the huge rocks blocking the river’s path. We scrambled down until coming to another small pool where we swam for awhile until it got too cold. While there, a family of lemurs came and perched in the trees just above us. They didn’t seem bothered by our presence and hung out for awhile watching. With lemurs becoming scarce, it’s rare to see them truly in the wild, away from any nature preserves or national parks.

After getting cold, we scrambled back up to the main pool and swam more until climbing back up to camp for dinner. After dinner we broke into small groups and had an opportunity for the kids to talk about life as a missionary and relationships with their parents. While being an ex-pat can be exciting and adventurous at times, it can also be hard on the kids. The kids talked about never living normal lives; they have few if any close friends, they generally move around the world against their will, their parents are always focused on work of the mission and often don’t have time for them. It was a good opportunity for the kids to share their feelings and how they work through them, and to let each other know that they were not alone.

Afterwards, everyone gathered around the campfire and sang and danced until late into the night.

The next morning we quickly packed up and got back on the road. The drive back to Mahajanga was quicker than the drive out, it took only a full day, but not without hiccups. We drove to the river where we had made our first camp without incident and stopped for snacks and a little swimming to cool off.

Shortly after starting out again, our troubles began. First, the truck ran out of gas. We had another car with us, that Hennie and Wilfred (Shelly’s brother-in-law) took off in to find gas, however, they were nearly out of gas also. Luckily, they found another broken down truck that they siphoned gas from and were back in 45 minutes. The battery on the truck was also dead, so it took us nearly forever, and all our remaining energy, to push start the truck and get it gong again.

Shortly after starting again, the clutch went out and the truck could barely shift. We now barely had any gas, with a dead battery, no clutch and threadbare tires. Then it started raining. The tarp over the back of the truck was tied up on top, and we couldn’t stop for fear of not being able to start again. The rain just poured down on all of us, but by then, no one really cared. Everyone just sat quietly and took it (needless to say, but I ended up throwing away most of the clothes I wore on this trip). When we got to the top of a small hill where the driver wasn’t so worried about getting stuck, we stopped and pulled the tarp down. But, this also had the side effect of making the back of the truck into a greenhouse.

It was then that the driver decided that he wanted to wait until after the rain stopped and the road dried before starting again. Everyone immediately objected, and luckily, Wilfred was able to convince him to keep going. The next stretch of road was crazy, it was probably good that the tarp was down and we couldn’t see. The truck was sliding, and fish-tailing, brushing up against trees, spinning, and barely avoiding getting stuck. But, the rain eventually stopped, we dried out and made it to the main highway before running out of gas again.

After Hennie and Wilfred got more gas, we made it back into town and back to Shelly’s parents. We all crashed hard that night. The next day we spent walking around town, shopping for souvenirs, and hanging out at the beach. The following morning we all packed up early and got ready to take our bus home. However, keeping in line with the transportation theme of our trip, the bus we had hired broke down that morning and they were scrounging to find two vans left in town that could take us home.

We left a few hours later than we wanted but still got out of town, and most everyone spent the ride sleeping. Twelve hours later I was back home in the compound, where I could finally crash (however, I got up early the next morning to meet some friends to go to a concert and ended up staying up all the next night… oh to be young again). It was a great trip, everyone enjoyed it, the kids had great attitudes.

Though the three days on the truck were obnoxious, it really made the trip. Sometimes the journey is the adventure.

Bribery

During my stay, Todd, one of Tom and Lauralee’s sons, came to visit for a couple months. It was great to have him around, we played a lot of ping pong and hung out with some of the other expats in the country together. I did not see Nate and Scott much on a regular basis, so it was nice to have Todd there to hang out with and talk to.

One late night, after leaving a friends house, we were driving home. Todd was a experienced “missionary kid.” Though now over 30, he had grown up in Africa, mostly in Swaziland and Kenya. His experience in foreign relations was vastly greater than mine; I had only youthful ignorance. Todd was also about 6’2″ 230 pounds.

At nights in Tana, groups of soldiers/gendarme would gather at street corners, in order to check people’s and car’s papers… and also to drink beer. Three Horses Beer was the beer of choice for most Malagasy. I am not sure the level of authority of these soldiers, but they carry AK-47s, and some level of authority comes with that.

As we approached a street corner that night, a group of soldiers were there, waving us to the side of the road with their flashlight. At the moment, I had the option, to just blow through and see what happened, or to pull over. Without much thought I pulled over. As we were coming to a stop Todd said to me, “I don’t have my passport with me.” When you’re doing everything right, it’s easy to talk your way out of a situation. When you’ve actually made a mistake, getting through it is much more difficult.

The chief of the soldiers walked up to my open window and asked for our papers. I gave him my identity card that I carried everywhere and substituted for my passport, and the truck registration. I also told him that Todd did not have his passport.

The chief’s eyes lit up with the possibilities of profit that the situation opened for him. “Well,” he said (I can’t remember if in French or English), “We will have to take your friend with us. However, you could give me a cadeau and go on your way.”

With bribery there is a great deal of moral and ethical dilemmas, and debate as to appropriate situations, or defintions. I had previously decided that I would not give bribes. Perhaps this was a great moral victory, or perhaps it was just youthful exuberance, but nonetheless, on this night, I carried out my decision.

“No, I’m not going to give you a gift”

“Then I will have to take your friend”

“No, you don’t need to take my friend”

“He does not have his papers, I must take him in”

Thinking that Todd could handle himself, “Ok, you can take him”

“No, no, no, just a small gift and you can go on your way.”

The group of AK-47 carrying soldiers surrounding the vehicle looked anxious. This conversation went on for probably 15 minutes, him asking for a gift, me refusing, him telling me he was going to take my friend. Eventually the point came when someone’s bluff would be called.

“We will have to take your friend”

“Ok, Todd, jump out, don’t go anywhere and I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Todd opened the door, and started to step out. Seeing that his bluff had been called (and probably not wanting to show up back at HQ, drunk, and with a huge American) the chief quickly handed me back my papers, “No, no, no, just go.” Todd closed his door and we quickly sped off.

Andringitra

It was pouring rain. At the height of rainy season, this was expected, but nonetheless, a serious hazard at this moment. The bus I was riding on, overloaded with nervous people and market goods, slipped and spun down the muddy road built precariously into the hillside. We were coming from a remote part a Madagascar, Andringitra National Park, and the twice weekly trips that this bus made comprised the majority of vehicle traffic on this road. As we rounded a bend the bus started sliding to the downhill edge a little closer that we were all comfortable with, and the passengers began yelling in unison, “Miala, miala!” We needed to get out of the bus.

We piled out. The women continued walking down the edge of the road while the men pushed against the back, downhill corner of the bus, in an ill-advised attempt to keep the bus on the road as it made its way through a few treacherous areas.

I had heard of Andringitra National Park through some other ex-pats who lived in country. At the time I was still really into rock climbing and Andringitra was a mythical place of endless granite rock walls. It was also supposedly one of the last pure wilderness areas of Madagascar, mainly known for those towering walls of granite and some endemic golden lemurs. The rock climbing there was said to rival that of Yosemite, which is a pretty bold claim, that I had to see for myself.

I read as much information as I could about the park in Lauralee’s old guide books and at one point even got a hold of the national park director in Ambalavao. Based on limited information (or, as it would turn out, no information) I booked my bus tickets to Ambalavao and headed on my trip.

I took the night bus from Tana in the hopes that sleeping through the 12 hour trip would make it go faster. I rode through the night, arriving in Fianarantsoa very early in the morning, around 4 am. Taxi-brousse stations in M/car are pure insanity, more so being a foreigner. Upon coming within 100 yards of a taxi-brousse station, you immediately become accosted by a group of men chattering at you loudly and pulling you around (interestingly, my wife and I had a similar experience upon exiting a ferry in the Philippines several years later). I don’t know a name for these men, but they apparently get paid for directing customers to certain bus companies. More than anything, though, they are just very annoying. I knew the names of a few bus companies, so upon nearing a bus station, I would just walk straight to that company, trying my best to ignore the dozen or so men yelling incoherently in my face.

Despite arriving in Fianar at 4 in the morning, these men were still there. I had already booked a ticket through to Ambalavao, and even had a hand-written receipt to prove it, so I was in no need for a personal shopper. Men crowded around the bus as it pulled in, banging on the windows and trying to open the doors. One man made it inside the bus, and began asking me where I was going and what I needed. I instead just talked directly to the driver and an actual employee of the bus company and after a few minutes of confusion; and them wanting me to buy an additional ticket to Ambalavao; I was able to get on a station wagon for the rest of my trip. Despite this, a man still tried to get into the station wagon demanding that he was my guide and I would pay for his trip. He was still asking for money through the window of the car as we drove away. A lot to deal with at 4 am.

I made it to Ambalavao a couple hours later as the town was waking up. I found a small roadside stand open and got some tea and bread to start my day. I took my time eating then slowly walked up the street to the national park office on the other end of town. When I got there it was still not open, so I just waited by the gate. Eventually a guard saw me and let me in and I was able to nap on a bench until the director arrived an hour later.

It was then that I found out that getting into the park was not so easy. At first, the national park director told me that I would have to drive my own car (which I did not have) or walk into the park, a 15-25 km trip. That not being an option we looked for another. Someone else at the office know of a bus that went out to the park on Tuesdays (the next day) and Thursdays that I could probably ride.

The director and I then left the office to inquire about the bus. First we drove and found Julio, a Peace Corps worker living in town whom I had coincidentally met previously in Isalo. We talk with him for awhile about the bus and arranged to meet up later. The director then drove me to a nice local hotel where I was able to get a room for the night. The room cost $9 a night, the most I ever spent for a hotel room, and at the time, being used to local prices, it seemed like an absurd amount. Julio met me later and we talked with the bus driver, got some food from the market and walked and talked a bit. I felt a little bad for Julio. About one year into his two year assignment he ran out of things to do and spent most of his time just hanging out. He seemed sad and disappointed with his overall experience and was ready to go. Thankfully, he had only one month left before leaving.

After leaving Julio, I spent more time just walking about town. Ambalavao is known primarily for two things: paper and architecture. Amabalavao is the home of the art of “Antaimoro” paper which they make at several places in town. Its a papyrus based paper, very rough, and usually with decorative flowers embedded within. It’s very popular with tourists. The house construction in Ambalavao is also very unique compared to other parts of the country. First, the houses have wooded porches with decorative carved railing. Second the roofs of the houses, rather than being thatch or tin as is common in all other parts of M/car, are made of clay tile, the only place in M/car where they build roofs this way.

The next morning I got up, stopped by Julio’s, and we went to catch the bus together. Julio was going to ride out also, but it turned out the bus was not staying long enough that day for him to do what he needed to get done. So I took the bus out alone, a 2 1/2 hour ride to the entrance of the park. The drive out was amazing. This was February and the heart of rainy season. The fields and rice patties were all lush and green. The drive was through rolling hills and valleys and next to tall rice terraces. The houses along the drive were all made of white mud/clay, another unique feature that I saw no where else and a striking visual effect among the green backdrop.

The entrance of the park had a nice welcome center, with some pictures of Madagascar and some examples of endemic plants of M/car. After awhile a guide arrived to take me into the park. With only about 2 1/2 days, I had to get started hiking if I wanted to see the park. I left my bags at a “safe” spot at the welcome center then we started out to two nearby waterfalls.

The area we walked through is called the Namohly Valley and is one of the prettiest places I have ever visited. Everything growing was bright green, the streams all full and rushing, high rice terraces everywhere and even taller granite rock walls, and red and white mud villages. We walked through the farms and villages, into the rainforest, and up the hillside to about the mid point of the two waterfalls.

My guide, Martin, was great, with endless energy. On our walk he told me the legend of the waterfalls. There were once a king and queen who try as they might were unable to have children. They consulted the local witch doctor who told them they must journey to the waterfalls far away and when there, bathe separately in the two waterfalls and sacrifice a bull. The made the journey, taking an all black bull with a white stripe on its forehead with them. They bathed and sacrificed the bull and returned to the village. They went on to have 8 children. The waterfall is said to have taken on the shape of the white stripe on the bull’s forehead. (By the way: the perfect family in M/car is said to be 14 children, 7 boys and 7 girls, a daunting task).

After spending some time at the waterfalls, we hiked back through the guide’s village, Antanafotsy, picked up my stuff at the welcome center, then went to guest house where I there was a room I could stay in. We agreed to meet in the morning at 7 to hike to the highest accessible point in M/car, Pic Boby. (There is one other mountain in Madagascar higher, however, it is extremely difficult to get to, is taboo to climb, and the only story I’ve read of someone climbing it ended with him being carried out by local villagers).

My guide knocked on my door at 6:15 the next morning, and told me he had been there since 5:30 and was apparently anxious to get get going. Though I was hoping to sleep in a bit, I reluctantly got up, hastily ate some fruit I had brought for breakfast and we got on our way at 6:30. The rising sun enhanced the beautiful colors of the villages and rice fields, making the whole valley look even more beautiful than before.

We hiked back towards the waterfalls of the day before and up a ridge to the side to a high plateau. At 7,000 ft, this was the highest plateau in M/car and also the only place in the country where blueberries grew. All across the valley and in the rest of the park, wildflowers and aromatic plants grew everywhere. Most prevalent were orchids, which grew like weeds. This is where most people spent the night, but having only one day and no camping gear, we pressed on.

All along our right side as we hiked were these huge granite cliffs, about 1,000 feet high. They towered over the whole valley and stood guard along our hike. This, apparently, was the mecca of Madagascar climbing. With no climbing gear and having, unforunately, met no climbers so far on my trip, I continued walking, left to stare in amazement. We hiked up through a small break in the cliffs where steps had been carved into the rock. We scrambled up this and most of the rest of the way to the top. We finally reached the peak after 10 miles and a 4,200 foot elevation gain. Pic Boby is 8,720 feet high. We paused a moment to rest and try to take in the view. We were surrounded by clouds so there was not much view to see.

We then quickly made our way back down, just in case the clouds were a sign that a storm was coming in. On the entire hike we made very little stops. On the 10 miles hike back, we made only one stop, at about 2/3 of the way.

Back at the guest house I noticed a funeral taking a place. A body had been laid, covered by a white sheet in a small grove of trees. Many were gathered around dressed in very colorful clothing. The women surrounding the body were singing. My guide told me that they would mourn for several days before taking the body on a long journey to the tombs.

The next day the bus was coming for market day and would be my ride home. I slept in, took my time packing up my things and cleaned up my room. I went over to where the market was being held and looked around at what they had. It was a pretty pitiful market with very little fruits or vegetables combined with the addition of manufactured goods brought by the bus in town. I found out when the bus was leaving, then went walking for a bit. I found a quiet bend in the river a swam in the cool water for awhile, soothing my aching muscles and joints.

I have to say again, that Andringitra was absolutely beautiful. Certainly one of the most beautiful places in the world. The area around the guest house was a lush valley of grasslands. A few small rivers ran through the valley. The granite cliffs bordered one end of the valley and foothills and rainforests edged the other sides. The valley had been farmed for centuries so most of the hills had been carved with rice terraces. Being the middle of growing season, the rice was high, think and green. Everything in the valley was so green. It was quiet, peaceful, relaxing.

I went backed to the guest house after swimming where I spent the rest of the day napping and reading. I went out later in the afternoon and waited for the bus to leave. It finally left around 6:45 when it began to rain. This brings me back to the start of the story.

As the bus was driving along some sections of the road it would start to slide down sideways across the road the steep dropoff on the downhill side. All vehicles in M/car have bald tires. As we started to slide, everyone on the bus would begin yelling, “Miala! Miala!” We need to get off! The bus would stop and we would all pile out (except the poor driver). As the bus would begin driving again, we would all push on the sides of the bus as it drove through some of the more treacherous parts to keep it going straight and on the road without sliding over the edge. In M/car, life is just different than in the U.S. After a while of getting used to this, you fail to notice at the time, just how strange your actions can get. Pushing on the side of a bus down a muddy road during a thunderstorm just didn’t seem that odd a the time. But in hindsight, I feel lucky to be alive.

After the harrowing one hour bus ride, we made it back to town in now, a complete downpour. I had intended to try to take a bus back to Fianar that night, but being late I had to stay. I went to a restaurant for dinner and found Julio there, so I had dinner with him and he led me to a cheap hotel where I could stay for the night. It was by far the worst hotel I’ve ever stayed in. It had a bed, a sink, and a urinal and smelled like a room that had only a bed, a sink, and a urinal.

The next morning I caught a passing bus back to Fianar. I really didn’t know much to see in Fianar, but since my week had been cut short in Andringitra, I decided to spend a day checking it out. What really drew me there were two things:

First, Fianar is the home town of Pierrot Men, the most famous Madagascan photographer. He brilliantly captures Madagascan life in beautiful photographs that are found nearly everywhere, but especially in his home town. Secondly, the only running train at the time in all of M/car was a train from Fianar to Manankara. It was supposed to be one of the most beautiful trips in the country. Unfortunately, due to timing and the unreliability of the only train in M/car, I was unable to make the trip.

I took a day bus back to Tana the next morning. While, typically I liked riding the bus at night, as sleeping made it go a little quicker, riding during the day had the bonus of the opportunity to see the passing country side (of course, on the 15+ hour trips you got to see day and night). On this day I took the chance to see the country and rode a day bus.

Shortly after leaving town, and at the top of the first hill, our bus broke down. Perhaps it would be a night trip after all. After napping on the side of the road for a couple hours (again, another thing that didn’t seem odd at the time, but in hindsight…), a replacement bus arrived and we made the rest of the trip back to Tana without incident.

Sticking with the theme of the trip, I arrived late at night in Tana, in a complete downpour (perhaps there was a cyclone passing through and these last few days were the ancillary rain). I managed to find a taxi despite the time and rain. The location of where we lived made it impossible for the taxis to make it to the compound in the rain, so I got off in Amboditsiry and ran the last mile home, completely soaked and exhausted.

Isalo National Park

After checking into a hotel for the night in Toliara, we made our way to the bus station to try to arrange our trip to Isalo and back to Tana. The bus station was insane, as are all bus stations in M/car. We needed to (1) get a bus from Toliara to Ranohira, the city closest to Isalo; and (2) get a bus to pick us up on New Years Day a few days later. This is difficult for a couple reasons. First of all, we weren’t entirely sure that we could actually get someone to pick us up 4 days later. We were taking a chance on them just stealing our money. Secondly, on New Years Day, all the drivers will be sleeping off a night of drinking, so we would have to find the only bus driver in M/car not getting wasted on New Years Eve.

We proceeded down the row of buses and began talking with the bus companies. We explained our situation (in my broken French/Malagasy mix) and quickly booked a bus to Ranohira for the next day. Then we started looking for a bus to pick us up New Year’s Day. It was then that we found out that there would be no bus drivers that day. With no bus, we had to quickly change our plans. There had been a man following us around this whole time saying that he had a car to take us to Ranohira. We had been ignoring him because it sounded fishy, and it would cost 450,000, ~$45. Realizing that we would now need to leave Ranohira a day earlier than planned, we decided leaving right away would be better than waiting until tomorrow. We found the car, negotiated them down to ~$20, then ran back and cancelled our bus trip to Ranohira. We also quickly found a bus that would pick us up on New Years Eve and booked three seats on that.

The car was leaving immediately, so we went back to the hotel, got our stuff, cancelled the room, quickly said goodbye to Tomasina, stopped at a store for some supplies, and got back to the car before they left. We hopped in the car, picked up the front seat passenger and left town. It turns out the driver and passenger were cousins heading back to Tana, just looking for some extra money for their trip. Worked out for us.

The trip was quick and smooth, partly because our driver seemed to be friends with all the police. We had an interesting event along the way. We pulled over on the side of the highway near a small village not near any major town. After a few moments a woman came out from the jungle. The driver gave her three glass bottles and 25,000 franc (~$2.50) and the woman handed him a baby lemur! Lemur trafficking is highly illegal, and it was amazing that the woman would do it for so little. The rest of the trip, the lemur was kept at the legs of the passenger, a gift for his niece.

The trip was a nice few hours, we were all grateful to be riding in a car. The driver knew of a decent hotel in Ranohira and dropped us off there. We booked a bungalow, then went to the visitor center to arrange a guide. The tourist services at Isalo were pretty nice. There were many certified guides and camping gear was also available for rent. We arranged a guide, porters to cook and set up camp, and camping equipment. We would take a three day trip at a total cost of about $25 each.

We went back to our hotel just before thunderstorms hit. We sat in our room looking out as one thunderstorm after another rolled past. Being out in the grasslands, I imagined that this was what the settlers in the west must have seen as they came across the Oregon trail. We could watch the storms come and go and the driving rain in between. As the sun set, the whole sky glowed red in the mist and low clouds of the storms. It was one of the most amazing sights I have seen, and sadly one my camera could not capture.

The next morning we started out on our three day trip. We packed our clothes and went into town to get some bread and tea for breakfast from a roadside stand. Our guide met us there and we started hiking through the grasslands along the face of the hills.

The park consisted of a massive area of sandstone formations that rose out from an otherwise barren landscape. The eastern edge of the park formed a wall of stone, like the massive ruins of an ancient fortress. Small canyons broke up the wall, gates through which we could cross into the wilderness of the interior.

We walked north, parallel to this wall across rolling hills and small rivers. We came across small villages along they way, and watched as farmers prepared their rice fields for planting by running cattle around in the mud. We also saw the makeshift distilleries where toaka-gasy is made, an alcohol so primitive and strong it kills hundreds each year. We stopped at a grove of mango trees where we would camp for the night. We set down our stuff and once the porters arrived, we set out to explore a couple canyons.

The two canyons we hiked to were the Canyon des Makis, and the Canyon des Rats. Makis was heavily forested and we walked under the canopy and through the jungle. While in Canyon des Makis we were fortunate to see some ring-tailed lemurs lounging in the trees, grooming each other.

Canyon des Rats was much less forested and filled with giant boulders. We crawled up, over and around these boulders, as far as we could go when we came to a bright, open pool. We swam in the cool water and climbed up the canyon walls to jump in. We ate a snack of egg and tomato sandwiches, and pineapple so sweet it burned our mouths. Nowhere have I found pineapple that tasted so good. After our ‘lunch’ we all napped on the sand and relaxed the rest of the afternoon.

Late that afternoon we hiked back to camp where we found a fantastic meal being prepared for us by the porters. We had a tea and ramen appetizer, followed by the standard rice and chicken loaka. As far as cuisine goes in M/car, you have two food groups: rice and loaka (loosely translated as: stuff you put on rice). Rice is most important; you have not eaten until you have had rice. Our meal was finished off with some bananas flambee. Needless to say, we slept full and happy that night.

Breakfast the following morning was again bread and tea, before we began our hike back up the Canyon des Makis. Once through the jungle and into the canyon we hiked for about a mile and a half over, around, and under every rock and boulder. Deep into the canyon, we finally got over the last of the boulders and began walking along the small stream that flowed through the canyon.

This part of the canyon was very narrow, with sheer cliffs going up hundreds of feet on both sides. More often than not, there was no room to walk along the creek, so we just took off our shoes and walked through the water and mud up the canyon.

Remember, Scott had only brought sandals on this trip, and badly sunburned his feet on our long walk to Ifaty. While in Toliara, before driving to Isalo, he had bought some wool socks to wear with his sandals. Scott, now dressed in his socks and sandals, walked ahead of me tromping through the creek, not even bothering to take off his socks. The image is burned into my mind, and is so funny, that I could barely write about it in my journal later, without choking in laughter.

We eventually were able to hike out the side of the canyon, and onto the high prairie of the interior. It was then that our guide informed us that he had never taken this route before, but thought it would be a good time to try it since we looked like a strong group. We hiked across a few more small canyons before eventually coming to a trail. We hiked until we came to our second campsite.

This campsite was very well built. It had a flushing toilet, running water, flat tent sites and stone picnic tables. We chatted with some other campers then headed for a swim. The first pool we came to was called “Namaza.” It was a deep, dark pool, surrounded by high, dark rock walls, with a beautiful waterfall flowing into it from above. We swam, and jumped from the rocks, the cold water soothing our sore muscles and joints from the last two days. Each day we hiked about 9 miles. We then swam in Piscine Noire; a slightly muddy pool, with a warm waterfall; and Piscine Bleu; a small, crystal clear pool.

We finished off the day with large plates of spaghetti and again, bananas flambee for desert. We woke up the final morning of our hike and immediately started off with a long staircase, back up to another long prairie. On this day, we stopped at one of the most beautiful places I have ever been, the “Piscine Naturelle.”

The landscape we were hiking through seemed so barren, just grass and rock. It appeared in hospitable. Yet out of the wilderness, hidden in small canyons, were these amazing oases. This pool had a small water fall on one side, a rock wall on another, a small beach, and the exit creek with beautiful tropical plants on the other. It was such a surreal place. The seclusion of a place like this preserved their natural beauty and made it a cool place to visit.

After spending a good time swimming and jumping off the rocks, we hiked the rest of the way back to Ranohira and our hotel, stopping at a high overlook along the way. The experience was great; we found a good guide and porters that made amazing meals. Each oasis that we came to was more amazing than the next. Exploring the entire park would have taken months, but I was glad we could explore even a small section.

The next day we pulled ourselves out of bed and waited along the side of the highway for our prearranged bus that we hoped was coming. After a two hour wait, we found our bus and hopped on. Our bus was so loaded down, that it couldn’t make it through the largest pot holes on its own, so every once in a while we would all pile out of the van and push the bus through the mud. After a couple hours we were all dying of laughter. We laughed so much on that trip.

This may have been my best trip in Madagascar, though I loved everywhere I went. Being with Nate and Scott was a lot of fun and the places we visited were just amazing.